The True Path to Diversity

by Kyah Hawkins

The murder of George Floyd turned the United States and the world into a state of chaos. He wasn’t the first person to lose his life to police brutality and unfortunately, probably won’t be the last. His death sparked many conversations about the racist violence and just plain racism that Black People endure while living in the nation. In the world of archives, conversations began about how to document the lives of Black People during this time and how to bring the hidden stories already acquired to the main dialogue of the archives' story. At the Legacy Center, over the last several years we’ve been delving into our own stories of diversity in the collections, exploring the different types of diversity that are documented in our archives and how those people and their identities had an impact on the College and the medical profession. As the events took over the media, we began focusing on the racial diversity that Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania experienced. The work may never be done but while exploring the collection some interesting stories struck a nerve with me, considering the state of the world.

Dr. Daisy Estelle Brown Bronner: From Seminary to College

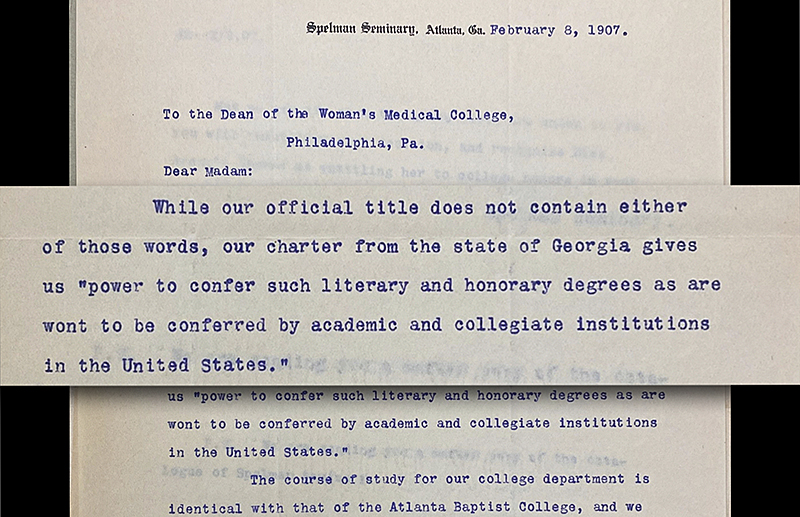

In 1907, Daisy Estelle Brown Bronner was readying herself to graduate from Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP). Four years prior she graduated from Spelman Seminary in Atlanta, Georgia with a Bachelor of Arts. In February of 1907, WMCP received some correspondence from the Spelman Seminary which revealed that the medical college would not accept her degree since the school’s name was Seminary, not College or University. This was later confirmed by both Harriet Giles, Spelman Seminary President and Dr. Clara Marshall, Dean of WMCP.

Spelman Seminary writing to Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1907.

Giles explained that despite not having the name of college or university, the charter given to the school by the State of Georgia expressed that the seminary had the “power to confer literary and honorary degrees as are wont to be conferred by academic and collegiate institutions in the United States.” The curriculum at Spelman was identical and even taught jointly with Atlanta Baptist College. While Spelman Seminary (later renamed Spelman College) was an all-Black women’s college, Atlanta Baptist College (later Morehouse College) was an all-Black men’s college. Spelman’s solution was to have Atlanta Baptist College give Brown an honorary degree from their school. In the end Daisy was able to graduate from WMCP with her medical degree.

Dr. Brown Bronner’s alumni file allows this story to be told although it doesn’t document her experiences at the college. But this one small problem offers an insight into the conditions of Black women pursuing degrees in higher education, they didn’t have many educational options overall. They did not have the many privileges to be taught by other Black doctors or have many Black students in their class at WMCP. Daisy was the lone African American student to graduate in 1907. Luckily, her undergraduate institution was supportive in her graduate endeavors and made sure that she pursued her plans of graduating from medical school.

Dr. Pauline Dinkins: One of One

The year of 1919 was a momentous year for women’s rights. In May of that year the country was mere months from ratifying the 19th amendment, granting women the right to vote. The idea of suffrage should have had women excited to participate in American politics finally as full citizens. Pauline Dinkins was not feeling the vibes. She was the only Black woman in her class pursuing medicine at WMCP. In her initial letter to Dr. Martha Tracy, dean of the college, Dinkins asked that her degree be mailed to her so that she may take her certifications exams to practice medicine. She had made the decision to not attend any of her graduation events, including the graduation ceremony itself. She cited that she did not feel a part of the class as the sole Black woman among them. She wrote “it simply infuriates me to hear one ill word said about the Negro race.” She explains an incident in her junior year that changed her perspective when a Black woman with arthritis was used in one of her clinical lectures and as arthritis can affect anyone despite race, the lecturer credited that as her reasoning of the ailment. Dean Tracy did not offer much sympathy to Pauline’s sensitivity. Instead, she stated “It is unfortunate for you that you take the attitude you do in regard to scientific facts stated concerning the Negro Race.” Her point was that since Pauline received a scientific education, she should be able to separate her personal feelings and her education.

Tracy encourages her to become a “worthy member of her race” by practicing medicine and leaving her own personal feelings at the door. Tracy’s statement almost sounds like she’s encouraging a Black woman to forget her racial identity because science proves they are the weaker race. For Pauline, the classes at WMCP enforced that Black people were not made for the medical profession, both scientifically and socially. She wrote that she forced herself to stay enrolled at the school because the material was not sensitive to her. She did not have anyone to turn to express her emotions.

Dr. Virginia Alexander and Fellow Students: Walk out for Equality and Disrespected No More

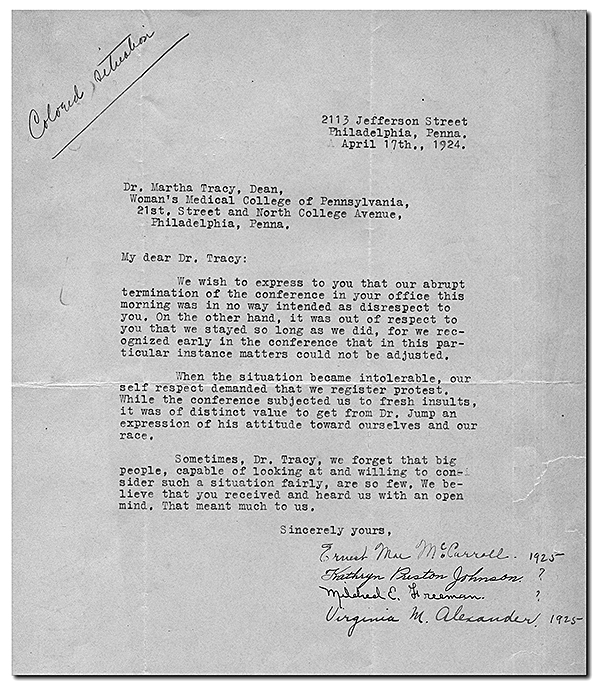

E. Mae McCarroll, Kathryn Preston Johnson, Mildred Freeman, and Virginia Alexander to Martha Tracy, 1924.

In a room full of students in Dean Martha Tracy’s office, in 1924, one white, male professor made four students feel uncomfortable and disrespected. These students were Virginia Alexander, E. Mae McCarroll, Kathyrn Preston Johnson and Mildred Freeman. Virginia Alexander would become one of the college’s most successful Black alums with her medical work in Philadelphia. She and her fellow students wrote to Dean Tracy about their feelings on the matter in a letter signed by each woman. They walked out of the lecture when they felt ostracized and mocked. In their complaint they wrote “we forget that big people, capable of looking and willing to consider such a situation fairly, are so few.” Implying that Tracy would be that “big” person. This was a major incident that shocked the students back to reality that people still were not used to African American women in the medical field. In Dean Tracy’s response, found in Alexander’s alumna file, she wrote “I appreciate your writing me, but regret that you misunderstood what I believe to be Dr. Jump’s real interest in you and your work.” This letter was only addressed to “my dear Miss Alexander” and totally ignored the feelings of four of her Black students. At the Legacy Center, we have not found evidence of Tracy replying to the other students or if this was the first incident of its kind as well as if the matter continued to be discussed which can be researched further in the future. But one thing is known that two of the students who signed the statement did not graduate from WMCP, Mildred Freeman and Kathyrn Preston Johnson. We do not know if this incident was the reason that they decided to leave the college, but it may have been a contributing factor.

From the accounts from 1907 and 1924, the social climate at the school was not tailored to the needs of Black students since they didn’t make up a huge percentage of the class. They did not have Black faculty members to look up to that could relay experience and mentor them. This does not mean that they did not have opportunities to attend all-Black medical colleges, although a few existed such as Meharry Medical College (founded in 1876) and Howard Medical School (founded in 1869). Very few women seemed to attend these schools in the early twentieth century. Even though the school being all-Black meant that would have accommodated Black people and their medical experiences. A fair conclusion is that the Black women who attended WMCP favored a school that catered to their identity as women over that of being Black. Despite them making the decision, the school was not as accommodating to their racial identity.

Dr. Martha Tracy: Silenced Voices Can’t Be Heard

Combined with the experience of Pauline Dinkins in 1919 and the four Black students in 1924, Dean Martha Tracy was a white woman who exhibited some subtle institutional racism. As she told Pauline Dinkins in her reply, she knew “scientifically” that Black people had to prove themselves more in the profession and to remove themselves emotionally. Her reply to Virginia Alexander in 1924, the only one of the four students who received a reply (that we know of), blamed the students for the feelings they had towards the words that Dr. Jump said during the infamous lecture in Dean Tracy’s office. This conclusion may not be completely correct and could just be two isolated incidents. More research can be done in the collections such as faculty meeting minutes, could shed more light on these issues. But it is important here at the Legacy Center that we be proud of the diversity but also call out when the administration was not too kind to those that made the school diverse. Especially, since in this century, we are still observing similar situations.

Student National Medical Association: Drexel Has Some Explaining to Do

In 2020, as a response to the incidents happening around the country, the Drexel Chapter of the Student National Medical Association (SNMA, student medical organization committed to supporting current and future underrepresented minority medical students link: ), delivered a list of grievances they had with Drexel and specifically the College of Medicine concerning their efforts in diversity and inclusion. This was not only a response to the murder of George Floyd but to how the university responded to the crisis. It was the instance that the conversation was about Black people and other people of color and yet Black students were not given a platform to speak. There have been far too many examples in history where discussions about Black people neglected to include their first-hand experiences. One student Brett Mitchell, a Black male at DUCOM, wrote in a Pulse interview (the DUCOM medical publication) “I wanted to share about the shortcomings in anti-racism in the curriculum.” Much like Pauline Dinkins in 1919, he worried about the curriculum including Black people in the medical conversation where it offers genuine solutions to the issues that affect the Black community. Mitchell wanted to hold Drexel accountable for the racial undertones found in the curriculum, just as the four Black students in 1924 when they approached Dean Tracy with their concerns. The students, much like in the past did not have the privilege to see people from the same background teach and lead a class to properly encourage them. Mitchell and another Black male student, Ayomide Igun, expressed their insights of being one of only a handful of Black men in their class. They spoke about how they were a part of a community that wasn’t acclimated to Black culture and made them feel out of place, much like Pauline Dinkins in 1919. The SNMA wanted Drexel to focus on the retention rate of Black men since many Black men don’t stay to the end since they don’t have the proper support.

Diversity Means to Not Question Your Place

I consider acknowledging and studying the past as the first step of creating change. History is a good indicator of what worked and what didn’t work. When the topic of diversity appears, the discussion usually shifts to the positive aspects of having inclusion but rarely speaks to the negatives. To fully understand every side, everything must be exposed to the light. When George Floyd’s unjust murder rocked the nation and the SNMA expressed their concerns and Drexel responded, the Legacy Center took it as a cue to look back in our own collections and reevaluate how we understand and show diversity. The stories expressed in this post are drawn from just few of the documents that can be used to investigate the lives of Black students in the twentieth century. Having diversity is not enough. Making those who are different feel welcomed and safe in spaces that they weren’t originally open for them is the true path to diversity. That is all that all the Black students in the past, present and future wanted, to not question their place.